techspatula.com portfolio of Ruth McAfee

UX / content / interaction design

techspatula.com is the portfolio of Sydney based UX, content, and interaction designer, Ruth McAfee

I have used this section to describe the experience of being a UXer. All words, images, diagrams, documents and prototypes shown below are 100% my own. Additional or more detailed examples can be provided on application.

I specialise in UX, and an interpretation of Agile Scrum methodology has been the preferred working cadence of every team I have joined in the last 7 years. No two implementations have been executed in quite the same way, and yet the challenges for UX are almost identical.

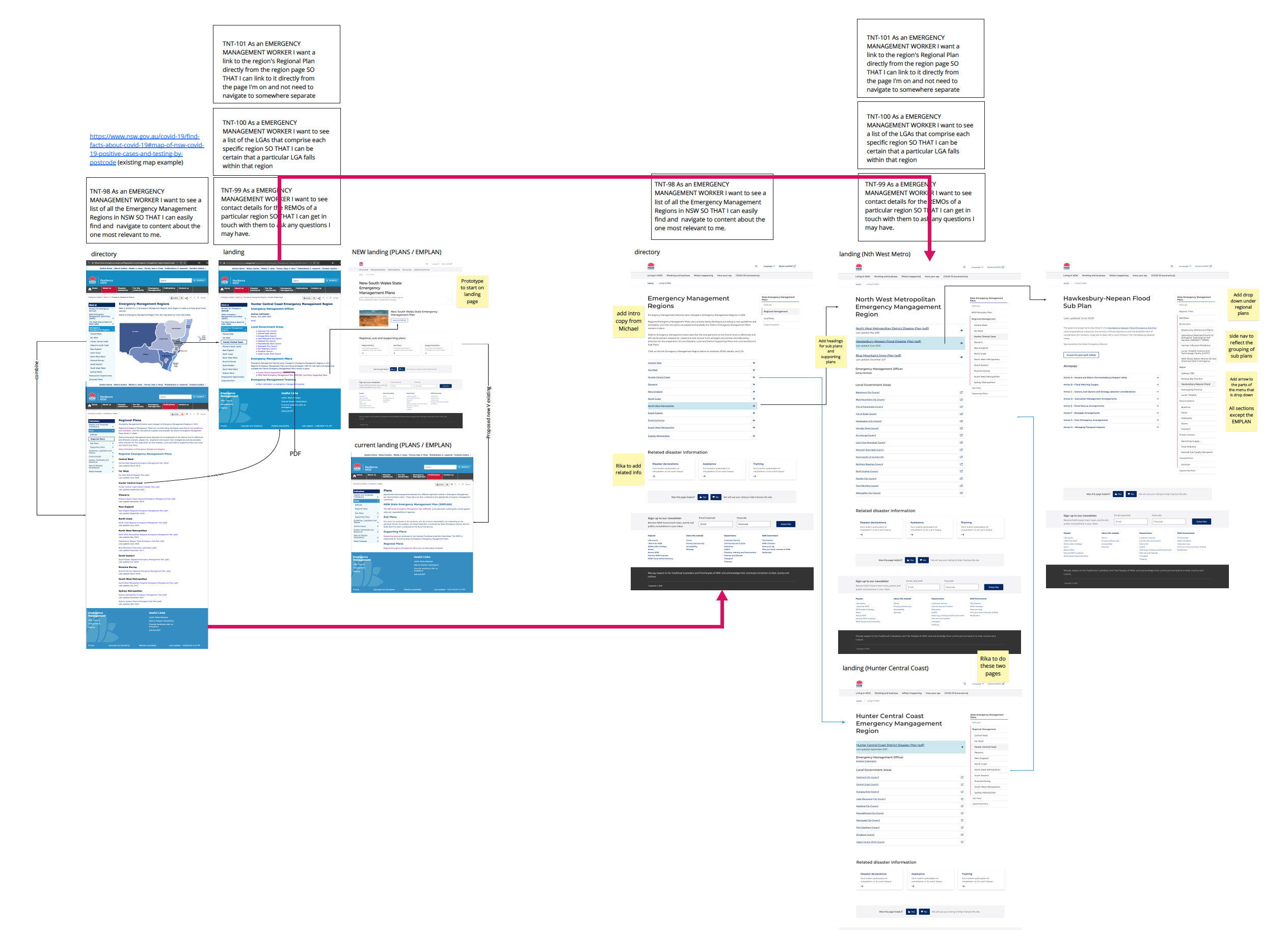

The first of these challenges is planning. Ideally, UX activities need to be completed at least one sprint ahead of design, which needs to be at least one sprint ahead of development. Workable roadmaps depend on a product backlog created with long-sighted forethought and vision - feeding into diligent sprint planning. (I'll explain why on the next slide.)

The second impediment for UX in Agile is the assignment of time to an ambiguous task. When productivity and performance are being measured by the number of tickets completed, and tasks are being assigned like a hand of cards to other team members, UX is put in an awkward position if poorly understood tasks remain tightly bundled and under scoped. As illustrated above in the HCD process, 'research' is an umbrella term for many activities - that all take time. Research activities usually include a current state assessment, identification and validation of the problem, and planning (which may involve writing a script, recruiting participants, and administration of privacy and security policies), all before the 'research' even begins.

Planning: UX activities inform UI and content design, which impacts navigation and IA, which comes before development and engineering. This is why UX activities need to coordinate with dev and engineering at the planning stage. In Agile product development, best practice is to share early and often, validate and revise - across each of the team functions. Unproven assumptions may waste hours of design or engineering time if work begins too soon.

Though its widely accepted that UX research will substantiate theories into validated stories, the right time to integrate UX into project management is not well understood. Starting with the product vision or end-state which was likely captured in a workshop with stakeholders, the product backlog records the outputs as requirements. Now we know where we are going, but we still don't know how to get there. Starting with the product backlog we need to be better at reconciling this. Including research spikes for UX to evaluate and determine the approach (such as steps 1 & 2 from the HCD process outlined in the study above) will result in more streamlined, engaging, and democratic sprint planning.

Estimates and sizing: I find that the variety and scope of UX tasks - which almost always fall into some kind of journey - are not well served by the punctuation of user stories or issues in Agile scrum. User stories are static, binary even, like a photograph stripped of its context. Agile User Stories were invented for the production of code in software development. By comparison, User "Experience" relies on wholistic recognition of the situation, the need, and the job to be done - or in a single word, empathy.

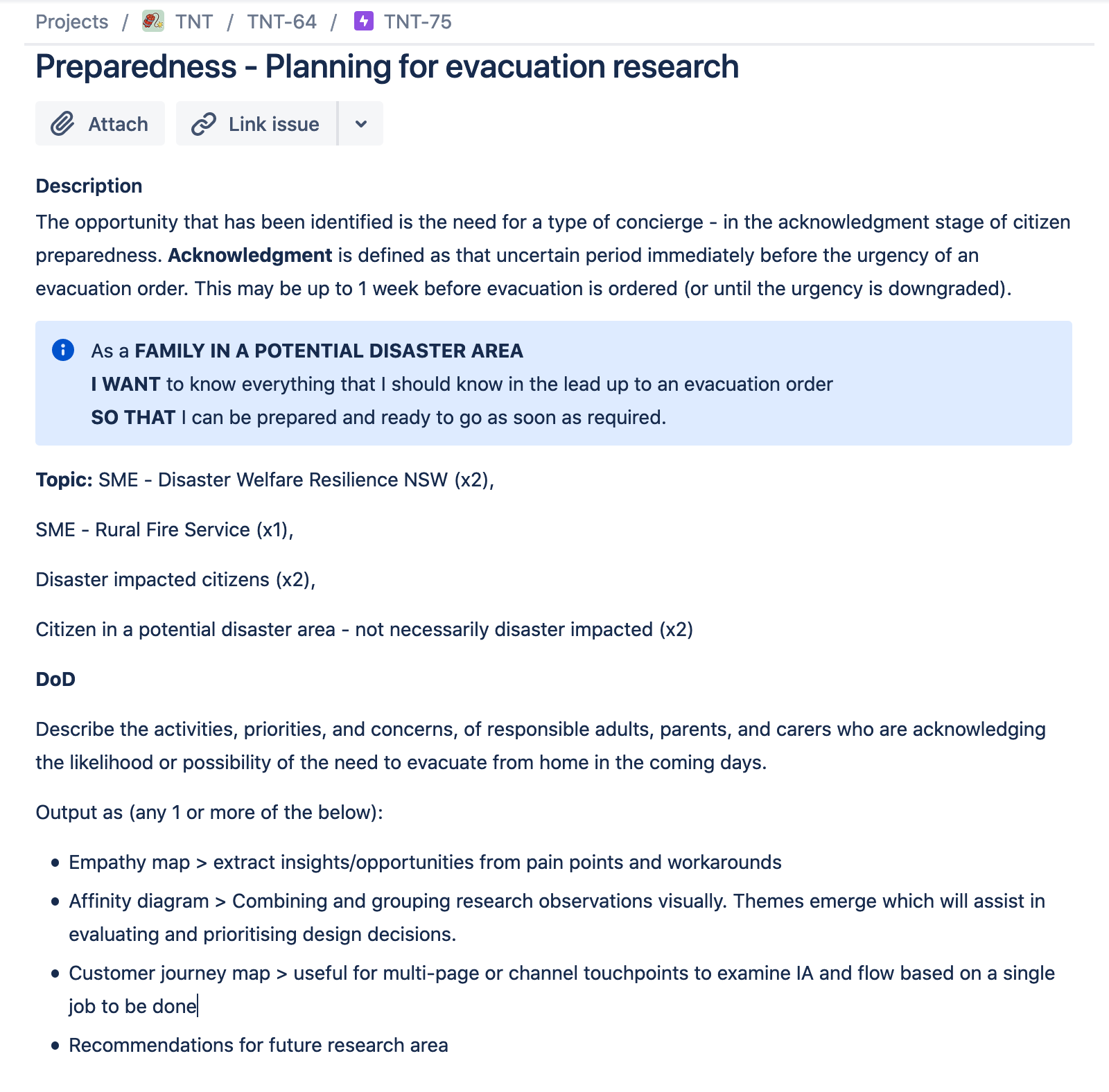

User Experience ~ User Empathy. When addressing the problem of estimating and sizing - as identified in the previous step, one simple approach is to replace user stories with job stories. Recently, while on contract at the NSW Department of Customer Service, I saw "Job Stories" in action. I first learned about these in the book "Content Design" by Sarah Winters published in 2017, where she describes the "Job Story" beginning with a situation and followed by a task, compared to user stories that address the audience first.

If you're reading about this for the first time, it might seem strange for a UXer to remove 'user' from the story, but in UX we ALWAYS think of the user first. The difference to me is that a job story also considers the users' situation, and thinks more broadly about what it is they need to get done. This is useful in understanding and preparing for a users' next move, or in bringing forward the context that has gotten them this far.

A second approach for mitigating sizing issues is to incorporate research spikes within the product backlog. A research spike provides visibility of the type and extent of research tasks to be done, while removing any uncertainty about when to incorpoate UX to the project workflow. Hence, the benefits to the team of this approach, are doubled.

The reality is brutal. It's the assignment of an issue estranged from its epic, because that's how code is done. Human centred design is not code. Without context, HCD is an oxymoron but the designer's responsibility doesn't change. We work long for less.

A project kicks off. The process (for delivering the thing we agreed to) has begun - except - before it exists, we can't know for sure if the market will like it.

UX (HCD) is precisely the methodology to alleviate this risk and to accurately refine and condense opportunities before engineering them.

UX activities, embedded from the outset are complementary to Agile project management. Let's do this.

References:

Content Design by Sarah Winters (formerly Sarah Richards)

Designing content for customer mindsets

Atlassian - Agile Manifesto

Lean UX by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden